New Study: Effects of neuromuscular training on female soccer athletes

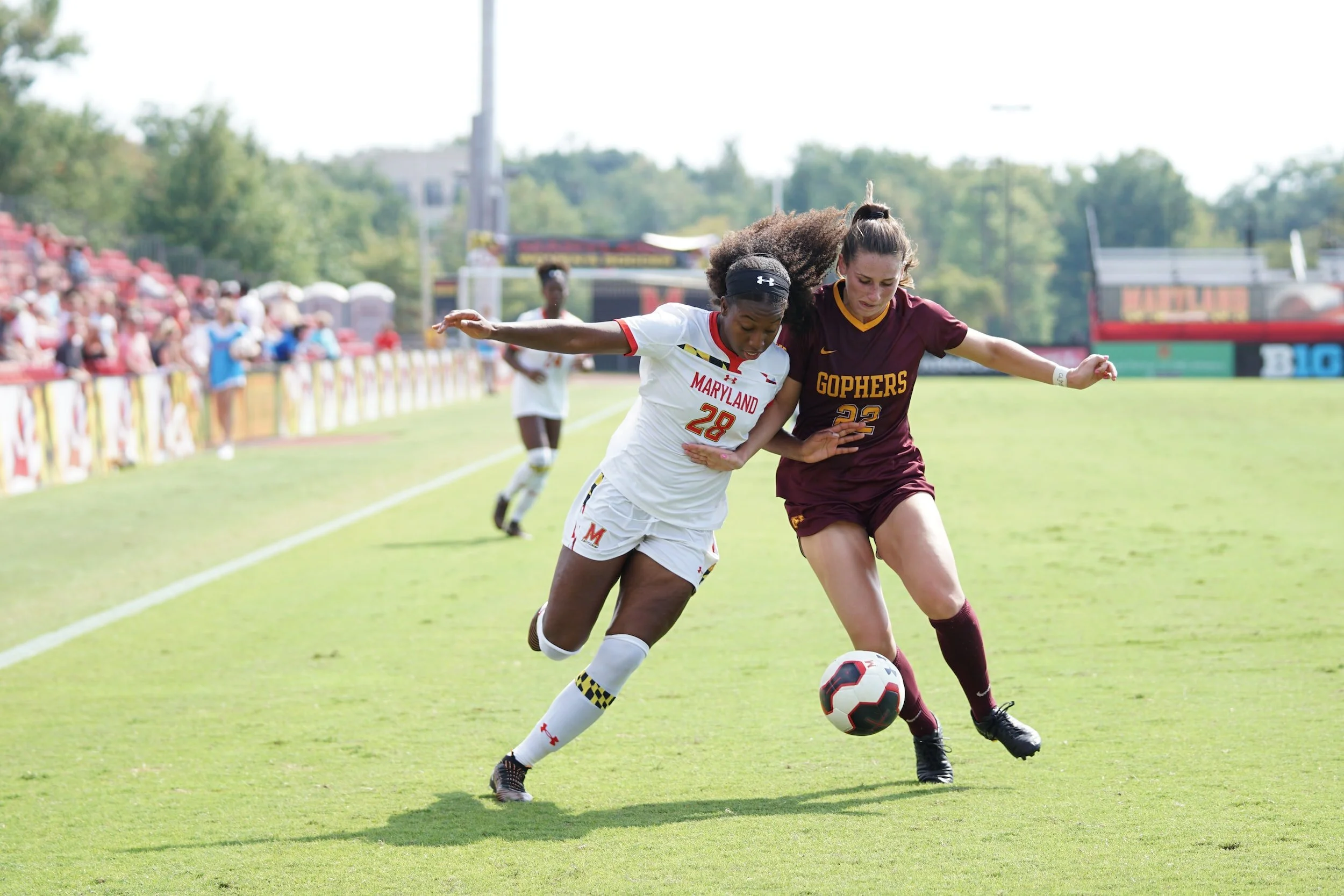

Lily Wilson blocks a defender during a high school match.

We get excited around here when we see a sports science study that’s focused only on female athletes. Why? There’s a measurable data disparity gap in sports science between male and female athletes.

This study was recently published in the May issue of Frontiers in Physiology, and focuses on the effects of neuromuscular training on performance and asymmetries in female footballers.

What’s “Neuromuscular Training?”

This publication from Myer et al defines it as:

"a training program that incorporates general and specific strength and conditioning activities, such as resistance, dynamic stability, balance, core strength, plyometric, and agility exercises with the goal to enhance health- and skill-related physical fitness components and to prevent injuries."

It differs from a “traditional strength training” program that focuses only on maximal strength gains. Neuromuscular Training is becoming the new normal in the sports performance world.

We know that footballers need neuromuscular development to help reduce the chance of injuries and increase performance, and while some training programs have shown good results, there’s been limited evidence.

Let’s dig into the study and the findings.

Effects of a neuromuscular training program on physical performance and asymmetries in female soccer

Authors: Alberto Roso-Moliner, Elena Mainer-Pardos, Antonio Cartón-Llorente, Hadi Nobari, Svein Arne Pettersen, Demetrio Lozano

Read the full study: PubMed

Soccer is a contact sport— collisions happen and we have to prepare our athletes for it.

Summary:

The study included 38 participants from two Spanish Second Division teams that were separated into two groups for 10 weeks. The experimental group performed three weekly neuromuscular training sessions, while the control group completed their normal strength and conditioning program. Both groups’ training sessions took the same amount of time (24 minutes).

Neuromuscular Training Protocol:

The experimental group completed a 24 minute, 6 exercise program done as a circuit (four sets with a work-to-rest ratio of 40 seconds to 20 seconds). The movements progressed in either load or specificity over 10 weeks.

The following movements were utilized:

Mobility: Lunge to Hamstring Dynamic Stretch, Standing hip out, 90-90 hip stretch

Stability: Star excursion balance, Side jumps + balance, Forward hop + balance

Anterior chain strength: Squat, Squat jump, Walking lunge

Lumbo-pelvic control: Front plank, Side plank, and Adduction (Copenhagen) plank

Posterior chain strength: Single leg glute bridge, single leg touch and hop, Scissors Lunge

Change of direction: Lateral shuffle, T-test, 505 test

Results:

The neuromuscular training intervention had positive impacts on lower body power and speed performance with notable improvements on maximal linear velocity and change of direction skills. There were slight improvements noted for ankle mobility, jumping skills, and a slight reduction in limb asymmetries.

Limitations:

Small study size (38 athletes) prevented the authors from differentiating the results by position

High level football athletes were studied, so it doesn’t necessarily give an accurate scope for the effects and impact on developing youth athletes

Our Thoughts:

If we can improve what leads up to 50% of high speed impacts, we can reduce the chances of injury.

This study highlights why focusing an athlete’s neuromuscular development — even for high level athletes — is important for sports performance and injury reduction.

Faude et al notes that jumping, cutting, and sprinting prelude more than half of the impact events on the field that result in musculoskeletal injuries. The more that sports performance coaches can prepare and skill-up athletes on jumping, cutting, and sprinting, the more we can reduce the chance of these impact events.

If we can both improve what leads up to collisions, and increase athletes’ body armor to protect themselves during those collisions, we’ll reduce their chances of contact injuries.

How this impacts our athlete performance program:

Good news! We’ve implemented neuromuscular training philosophies into our programs for a long time. We also measure our athletes’ performance improvements on a regular testing schedule for things like jumping, sprinting, change of direction, and knee health.

Our athletes would recognize most of the movements used in this study— to some of their chagrin (I know how a lot of you feel about the 90-90s, athletes, but you’re gonna do them, anyway 😅).

Just lifting to get strong… or going to a commercial gym for a bro session.. or endlessly running to stay “fit”… or training with someone that isn’t qualified does athletes a disservice.

It’s important to train using a program that balances neuromuscular training with strength training, especially as athletes go through puberty and continually re-learn how to move their bodies as they grow. And that’s what we aim to do at Raymer Strength— meet our athletes where they are at, learn how they move, and build them into better athletes than when they first walked through the door.

Interested in training with us?

We’re located in Central Indiana and train both in-person and online.

Drop us your details and we’ll get in touch.

Related:

References:

Roso-Moliner, A., Mainer-Pardos, E., Cartón-Llorente, A., Nobari, H., Pettersen, S. A., & Lozano, D. (2023). Effects of a neuromuscular training program on physical performance and asymmetries in female soccer. Frontiers in physiology, 14, 1171636. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2023.1171636

Myer, Gregory D. PhD, CSCS1,2,4,7; Faigenbaum, Avery D. EdD, FACSM3; Ford, Kevin R. PhD, FACSM1,2; Best, Thomas M. PhD, FACSM4,5; Bergeron, Michael F. PhD, FACSM6; Hewett, Timothy E. PhD, FACSM1,2,4,7. When to Initiate Integrative Neuromuscular Training to Reduce Sports-Related Injuries and Enhance Health in Youth?. Current Sports Medicine Reports 10(3):p 155-166, May 2011. | DOI: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1442

Faude, O., Koch, T., & Meyer, T. (2012). Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. Journal of sports sciences, 30(7), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.665940